From Paper to Pixels: How Screen Learning Compares to Print

Which team are you on: printed or digital books?

A few days ago, I began setting up research on students' study habits. While brainstorming questions I wanted to include in the survey, I started thinking about my university days and remembered all those bulky printed books, scripts, and meticulously sourced research papers. I was (and still am) definitely in the "printed books" team.

In this article

Introduction

As educational content increasingly shifts from paper to pixels, we must grapple with how this transition affects our cognitive processes.

Physical texts have always provided our brains with invaluable spatial and tactile cues, enhancing memory and comprehension. The act of physically turning pages, highlighting passages, and noting margins engage critical brain regions, aiding in deeper information absorption. In contrast, with their dynamic interfaces, digital materials might lead to a more superficial interaction, potentially sidelining intricate details.

Yet, the digital age is not all that bad. By incorporating strategic approaches like active note-taking and leveraging specific digital tools, you can optimise your digital learning experiences.

Keep reading to see how your brain processes information when you learn from a printed book and how you can improve comprehension if you study with digital learning materials.

How Your Brain Processes Information When Reading

Reading print offers an immersive experience, similar to meditation, as described by Anne Mangen, a literacy professor. She also says that

"it's healthy for us as human beings to sit down with something that doesn't move, ping, or call on our attention." (1)

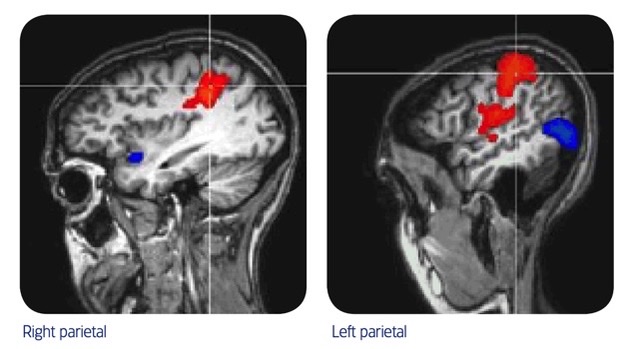

The tactile nature of a book and its unchanging content allows the brain to process without digital distractions. Research from 2009 by the marketing research company Millward Brown (2) found that the brain processes physical and digital materials differently. When participants viewed advertisements, print materials activated regions of the brain associated with processing emotions and visual-spatial cues, specifically the medial prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex, and parietal cortex.

Simply said,

"physical material is more "real" to the brain. It has a meaning and a place. It is better connected to memory because it engages with its spatial memory networks."

NB The red area in the images of the brain represents greater oxygenated blood flow (and hence activation) stimulated by physical ads. The blue areas are regions activated more by virtual ads. The “cross hairs” highlight the named brain region.

Another challenging feature of digital materials are LED screens and their constant flickering demand more from our eyes, leading to visual fatigue.

How to avoid it?

e-readers, like Kindles, attempt to mimic the paper experience by eliminating the need to scroll and using e-ink technology to reduce eye strain.

Comprehension and Retention in Digital vs. Print Reading

Digital reading, while fast and convenient, tends to lead to superficial comprehension. Studies (3) revealed that students, when reading digitally, often miss out on the details. This is because the constant exposure to rapidly shifting digital content can retrain the brain, leading to quicker but less thorough processing. This phenomenon is also known as the "shallowing hypothesis" (4).

The "shallowing hypothesis" suggests that recent media technologies have led to a decline in daily reflective thought.

The challenge of spatial mapping in digital reading, especially with scrolling, further hinders comprehension. Scrolling places additional demands on our working memory, limiting our ability to retain known and remembered information.

Why is that?

Have you ever had a written or oral exam and knew the answer because you remembered that this specific information was near the top left-hand page of a book?

This happens because our brains construct a cognitive map of the text. Now, imagine trying to construct a map of something with constantly moving landmarks, which is what happens when you scroll through the digital learning material. It's harder to map words that aren't in a fixed location.

Because of all these characteristics of learning from print and digital materials, print readers show superior retention of the story's chronological sequence compared to e-reader users.

So, how can you improve comprehension and knowledge retention if you are in the "digital books" team?

Strategies to Help Improve Comprehension and Retention

Here are a few ideas you can apply when learning from digital scripts. Yes, you can use them when learning from printed materials as well 😀.

- Focused Reading Sessions: Limit your reading sessions to specific time blocks and minimise distractions. Turn off notifications and choose a quiet environment.

- Highlight and Annotate: Use digital tools to highlight key points and annotate as you go. Revisit these notes periodically.

- Interactive Engagement: Engage with any interactive elements (e.g. interactive notes) in the text. They are often designed to enhance understanding.

- Take Breaks: Unlike print, screens emit light, which can strain your eyes. Follow the 20-20-20 rule: every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds. (20 feet 0 6 meters).

- Summarise in Your Own Words: After finishing a section or chapter, pause to summarise what you've read in your own words. This reinforces comprehension.

- Physical Notes: Sometimes, writing things down the traditional way (using pen and paper) can help with retention.

- Discuss: Engage in discussions about what you've read. Platforms like online forums, discussion groups, or even talking to a friend can be beneficial.

- Adjust Screen Settings: Opt for a warmer screen tone, reduce brightness, or use 'night mode' features in the evening to reduce blue light exposure and strain.

- Mindful Scrolling: Avoid rapid scrolling. Scroll deliberately, making sure you fully understand a section before moving on.

- Revisit Important Texts: Much like rereading a print book, revisit important digital texts periodically to reinforce retention.

- Interactive Quizzes: If the content offers interactive quizzes or assessments, use them. Testing reinforces memory.

- Create a Mental Map: Try to visualise the content structure, much like how you would recall a physical book's layout.

- Limit Multitasking: It can be tempting to switch between tabs or apps. Stay focused on one task to ensure deeper comprehension.

- Use Digital Bookmarks: Just as you'd bookmark a physical page, use digital bookmarks to mark where you left off or to highlight important sections.

- Practice Active Reading: Ask questions as you read, predict what might come next, or connect the information to what you already know.

Remember, as with any skill, improving comprehension and retention in digital reading comes with practice. By deliberately applying these strategies, you can get the most out of your digital and interactive texts.

Conclusion

While traditional printed materials offer a tactile experience that aids memory and comprehension, digital platforms provide unparalleled convenience and accessibility. Harnessing the strengths of both, while being aware of their challenges, allows for a holistic learning experience in today's academic landscape.

Key Takeaways:

- Physical books provide tactile and spatial cues that enhance memory and comprehension.

- Digital reading often leads to quicker but potentially more superficial comprehension, influenced by the dynamic nature of digital interfaces.

- Challenges like scrolling and visual fatigue from LED screens can hinder digital learning.

- Effective strategies such as focused reading sessions and interactive engagement can optimise digital learning experiences.

More about the topic in:

(1) Branfacts.org, "Reading on Paper Versus Screens: What's the Difference?" 2020

(2) Millward Brown. (2009). Case Study: Understanding Direct Mail with Neuroscience.

(3) Lauren M. Singer & Patricia A. Alexander (2016). Reading Across Mediums: Effects of Reading Digital and Print Texts on Comprehension and Calibration, The Journal of Experimental Education, DOI: 10.1080/00220973.2016.1143794

(4) Logan E. Annisette, Kathryn D. Lafreniere (2017). Social media, texting, and personality: A test of the shallowing hypothesis. Personality and Individual Differences (115), pp. 154-158